Build an OpenStack/Ceph Cluster with Cumulus Networks in GNS3

Build an OpenStack/Ceph Cluster with Cumulus Networks in GNS3

Introduction

I must have built OpenStack demos a dozen times or more over the past few years, for the purposes of learning, training others, or providing proof of concept environments to clients. However these environments always had one thing in common - they were purely demo environments, bearing little relation to how you would build OpenStack in a real production environment. Indeed, most of them were “all-in-one” environments, where every single service runs on a single node, and the loss of that node would mean the loss of the entire environment - never mind the lack of scalability!

Having been tasked with building a prototype OpenStack environment for an internal proof of concept, I decided that it was time to start looking at how to build OpenStack “properly”. However I had a problem - I didn’t have at my disposal the half-dozen or so physical nodes one might typically build a production cluster on, never mind a highly resilient switch core for the network. The on-going lockdown in which I write this didn’t help - in fact it made obtaining hardware more difficult.

I’ve always been inspired by the “cldemo” environments on Cumulus Networks’ GitHub and my first thought was to build on these for this task - however I wanted to use this as a learning tool, and the disconnect between the Vagrant code and a visual representation of the network layout meant I didn’t find this an ideal learning environment. I love Vagrant, but it’s unlikely you would use it in a production environment. However this sparked off an idea - could you use GNS3 to build a working model of an OpenStack cluster?

Enter GNS3

To answer this question I started to experiment with GNS3. I’ve played with it before to prototype some firewall configurations and other small network related tasks, but I had never considered using it for something heavy weight such as an entire OpenStack environment. However I had already established that it is a great tool for building visual network layous, and for interacting with the network (for example, you can right click on a network link and see a Wireshark trace of everything running over that link). In addition, testing out a few different configurations demonstrated a few things I hadn’t fully appreciated before:

- If you are running QEMU images in GNS3, they are run with the same fundamental KVM virtualization on which tools such as OpenStack and oVirt themselves are based - thus this ought to be possible to scale up.

- When you define a new QEMU machine image in GNS3, and drag that machine onto the canvas, GNS3 doesn’t create a full copy of the virtual disk image. Rather, it creates a linked clone of the original, meaning that only the differences between the original image and the copy on the canvas are stored on disk, saving space.

- This reliance on open source tools means you can interact with the disk images directly using tools such as qemu-img and guestfish if you wish.

- GNS3 creates neatly packaged portable project files, meaning you can easily backup and archive your work (or versions of it), provide others with a copy, and so on. Snapshots are also supported.

Overall, it seemed that GNS3 was a far more powerful virtualization tool than I had given it credit for, and actually well suited to the task I had in mind. However…

GNS3 Limitations

GNS3 does have it’s limitations, and obviously you’re not going to run things at bare metal or wire speeds inside it. Although GNS3 runs on macOS, Windows and Linux, I started my testing on Windows 10 and quickly discovered that all of the clever work performed by GNS3 happens in a special virtual machine - the “GNS3 VM”. This essentially is a specially customized Ubuntu Linux image designed to handle the GNS3 tasks, and if you are relying on this, then your QEMU virtual machines are running inside another virtual machine - the nested virtualization adding overhead and slowing things down.

Further, some of the functionality I had wanted to take advantage of in my work, such as snapshots and exporting portable project archives seemed to be fundamentally broken in Windows 10 - a tour of the forums seemed to indicate I wasn’t alone, though offered no solutions. However as soon as I installed Ubuntu Desktop on my test rig, all of these problems went away, so if there’s one thing I learned from this experience, it’s run your setup on Linux from the start.

Another thing worth factoring in (though not a limitation of GNS3) is that if you build out the full architecture I created, then you’re going to be running a total of 15 virtual machines on a single host. This means you’re going to need lots of RAM (my setup needed 48GB when fully operational) and fast disk (SSD highly recommended). If you don’t quite have enough RAM (I had 32GB on my test rig), you can run QEMU virtual machines in swap memory. Needless to say this isn’t recommended and is certainly going to decrease the life of your SSD - however if you don’t have a rig with 64GB of RAM to hand, this little “hack” will get you going where you might otherwise come to a grinding halt.

Goals

Having decided upon my platform it was time to set some goals for this exercise:

- I would use a minimum of VM images to build this infrastructure - in the end, just two were needed:

- The Cumulus VX 4.0 image

- The Ubuntu Server 18.04.4 Cloud Image

- There would be no “by-hand” configuration of any nodes in the virtual infrastructure - not even for authentication.

- All code used for the environment should be easily scaled to a real world production environment. In reality this meant two tools:

- Cloud-init - natively supported by most cloud images including Ubuntu Server

- Ansible - for all post-boot configuration work

- The final infrastructure would be based on the openstack-ansible project, and their documented “Ceph Production example”: https://docs.openstack.org/openstack-ansible/stein/user/ceph/full-deploy.html

- This infrastructure would feature 4 Cumulus VX switches in a spine-leaf topology, with a simple layer-2 CLAG configuration to ensure a resilient switched architecture.

- An additional Cumulus VX switch would be used as an out-of-band management network, with all nodes having eth0 reserved for out of band management.

Building the infrastructure

Having worked out the platform, tool set, and goal, the remaining task was to build the architecture itself. This was broken down into a series of clear stages, each clearly separate from the other:

- Adding the virtual machine images to GNS3

- Building the virtual infrastructure on the canvas

- Creating the cloud-init configurations for each node, and building these into an ISO for boot-time configuration.

- Configuring the management node - this is responsible for for DHCP and DNS on the management network, routing of traffic from the OpenStack infrastructure to the Internet, and running the Ansible playbooks over the management network.

- Configuring the out-of-band management network with Ansible.

- Configuring the spine-leaf switch topology with Ansible.

- Deploying OpenStack using the openstack-ansible playbooks.

Adding virtual machine images to GNS3

I’m going to assume that at this stage, you’ve got a fully working (and tested) GNS3 install on a suitably powerful Linux host. Once that is complete, the next step is to download the two virtual machine images we discussed in part 1 of this blog, and integrate them into GNS3.

In my setup, I downloaded the Cumulus VX 4.0 QCOW2 image (though you are welcome to try newer releases which should work), which you can obtain by visiting this link: https://cumulusnetworks.com/accounts/login/?next=/products/cumulus-vx/download/

I also downloaded the Ubuntu Server 18.04.4 QCOW2 image from here: https://cloud-images.ubuntu.com/bionic/current/bionic-server-cloudimg-amd64.img

Once you have downloaded these two images, the next task is to integrate them into GNS3. To do this:

- Select Edit > Preferences in the GNS3 interface.

- When the Preferences dialog pops up, from the left pane select QEMU VMs, then click New.

- Enter a name for the Image (e.g. Cumulus VM 4.0)

- Select the Qemu binary, and specify default RAM size for each instance (I used 1024MB). You can override this for each VM you create on the GNS3 canvas, so don’t worry too much about it.

- Select the Console type - I used telnet for both images.

- Finally browse to the image file you downloaded earlier. When asked if you want to copy the image to the default images directory, I prefer to say Yes.

Make the following additional changes once the images have been copied over:

- Edit each VM and set an appropriate symbol for it - this makes the canvas easier to interpret, but has no effect on the operation of GNS3. I used:

- :/symbols/classic/ethernet_switch.svg for Cumulus VX

- :/symbols/classic/server.svg for Ubuntu Server

- Change the On close setting from “Power off the VM” to “Send the shutdown signal (ACPI)” for the Ubuntu server VM’s - this ensures they cleanly shutdown when you close your GNS3 infrastructure.

With this stage complete, you can proceed to building your infrastructure on the canvas.

Build virtual infrastructure on the canvas

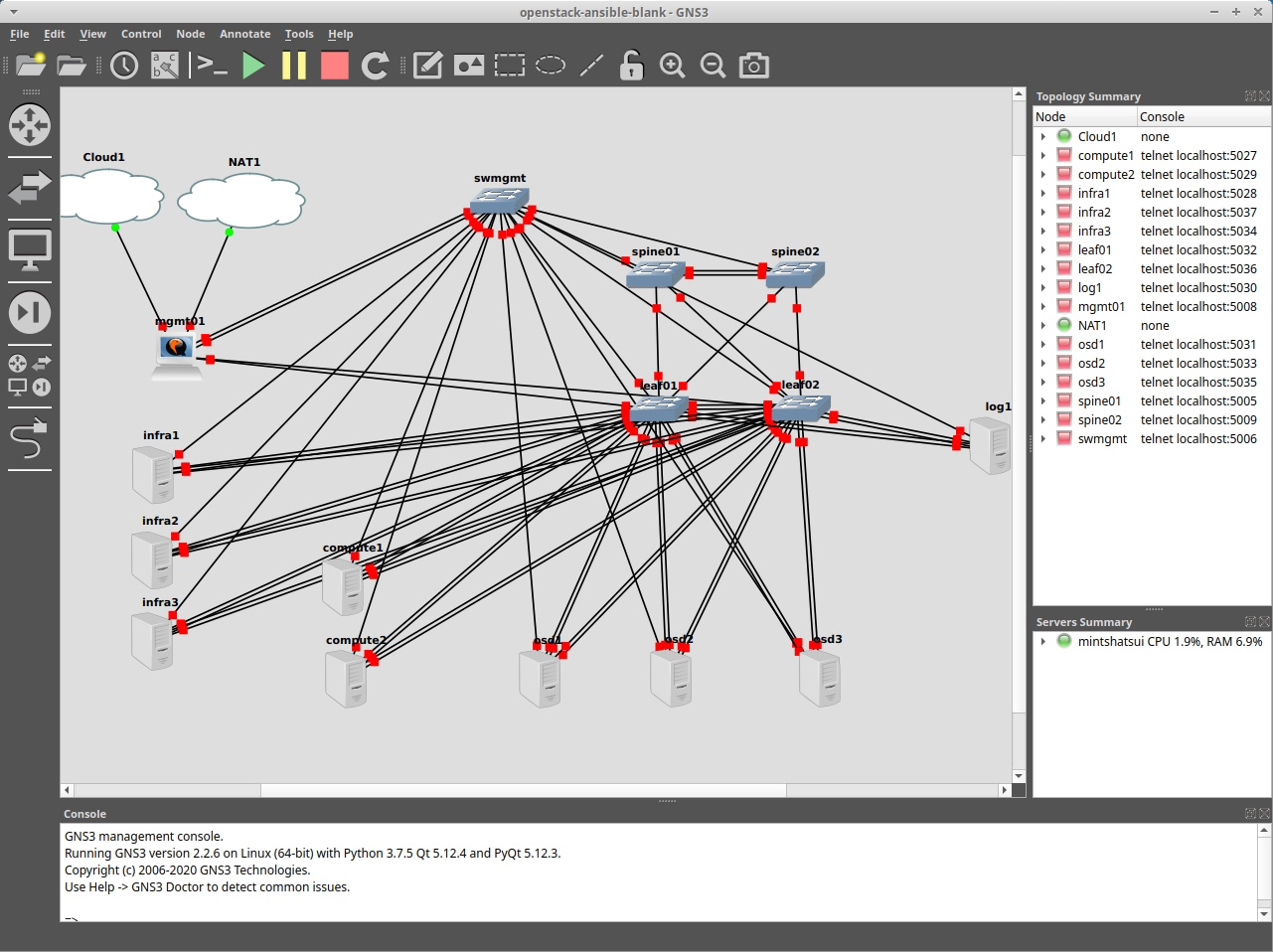

Once we’ve defined our QEMU VM’s, the real fun starts! We can now simply click and drag our infrastructure onto the canvas. GNS3 doesn’t support orthogonal lines for the connections, so it can be a little crowded by the time you’ve completed as complex an architecture as we are building here - however the effort is well worth it, especially when you consider that you can right click on any connection and sniff the traffic running over it! This is a great learning and investigative tool.

One important learning is this - GNS3 does not have the capability to edit the number of network connections on a device on the canvas once you’ve connected it up - you have to delete all your connections if you want to edit this property. Thus it’s worth taking some time to plan out the design or simply add more ports than you need.

You’ll also need to edit the amount of RAM some of the VM’s are allocated, and the disk sizes too. Also for our static DHCP allocations for the Cumulus VX switches you will need to set the MAC addresses recorded in the table below. Note that the sizes and values recorded in this table are the ones I have tested with - they should however be viewed as minimum viable values, and may need to be increased depending on how you want to test your virtualized infrastructure:

| VM Name | RAM (MB) | Primary disk (MB) | Secondary disk (MB) | Network interfaces | MAC address |

| mgmt01 | 2048 | 32000 | N/A | 8 | 0c:51:8c:6a:4a:00 |

| swmgmt | 1024 | 32000 | N/A | 24 | 0c:51:8c:35:f0:00 |

| spine01 | 1024 | 32000 | N/A | 16 | 0c:51:8c:7d:e3:00 |

| spine02 | 1024 | 32000 | N/A | 16 | 0c:51:8c:29:ba:00 |

| leaf01 | 1024 | 32000 | N/A | 48 | 0c:51:8c:2f:cb:00 |

| leaf02 | 1024 | 32000 | N/A | 48 | 0c:51:8c:3d:99:00 |

| infra1 | 8192 | 32000 | N/A | 5 | 0c:51:8c:5b:3d:00 |

| infra2 | 8192 | 32000 | N/A | 5 | 0c:51:8c:da:ec:00 |

| infra3 | 8192 | 32000 | N/A | 5 | 0c:51:8c:5a:3e:00 |

| log1 | 2048 | 32000 | N/A | 5 | 0c:51:8c:58:36:00 |

| compute1 | 4096 | 32000 | N/A | 5 | 0c:51:8c:16:f5:00 |

| compute2 | 4096 | 32000 | N/A | 5 | 0c:51:8c:89:13:00 |

| osd1 | 4096 | 32000 | 30000 | 5 | 0c:51:8c:c5:3d:00 |

| osd2 | 4096 | 32000 | 30000 | 5 | 0c:51:8c:39:61:00 |

| osd3 | 4096 | 32000 | 30000 | 5 | 0c:51:8c:55:a3:00 |

Note that all disks are created as sparse disks, and so will not occupy the amount of storage specified above. When I had fully built my demo environment, it occupied a total of around 112GB.

In general, the network topology is laid out as follows:

- Mgmt01 connects to both a Cloud and a NAT device in GNS3 - the NAT device provides fast connectivity, outbound, for all VM’s on the canvas. The Cloud device is very slow, but allows you to SSH directly into your management VM if you wish. You can leave this out if you prefer.

- On all other nodes, eth0 is connected to swmgmt, and is used for out-of-band management.

- All OpenStack VM’s have 5 Ethernet ports. After eth0 (management), the other 4 are used in bonded pairs for the two physical networks suggested in the openstack-ansible example document. They are wired up alternatively to leaf01 and leaf02 in pairs, starting at eth3 on these switches (eth1 and eth2 were used for testing purposes in the early stages of the design and are not assigned in the current version).

- The high numbered ports on the switches are used for the interconnects between the switches that enable MLAG to operate.

Your resulting canvas should look something like this:

Creating cloud-init configurations

Once you have built your infrastructure on the canvas, the next task on our list is to build a set of cloud-init ISO images. Although the Cumulus VX images have a well known default username and password that we can make use of, the Ubuntu images do not - in fact they have no default password set at all, as they expect to get this from the cloud orchestration system (e.g. OpenStack, Amazon EC2, etc.). Fortunately for us, cloud-init is built into the Ubuntu cloud images we downloaded, and can perform any of a number of tasks, from setting a default password, to configuring the network interfaces (even bonding can be set up!), and running arbitrary commands. On the first boot of every VM, cloud-init searches a well known set of locations for its configuration data, and one of these happens to be an ISO image attached to the VM. Thus we can create a small, unique ISO image for each VM that does the following:

- Sets the hostname for each VM

- Sets the password for the default user account (ubuntu)

- Adds an SSH public key to this user account for passwordless management

- Changes the boot parameters of the VM to use the old eth0, eth1,… style of network interface naming

- Installs Python (to enable further automation with Ansible later on).

In addition, for our “management” VM, our cloud-init scripts go even further, both installing Ansible and even cloning the GitHub repository that accompanies this article to the home ubuntu user’s directory.

Rather than go through the code in detail here, we’ll leave you to explore it yourself, as it is all available here: https://github.com/jamesfreeman959/gns3-cumulus-openstack-ansible

Makefile’s have been placed at appropriate places in the directory structure to help you get started easily. The process for building the ISO files is as simple as:

- Clone the Git repository to the machine running Ansible:

git clone https://github.com/jamesfreeman959/gns3-cumulus-openstack-ansible

- Change into the clone directory, and run “make” to generate an SSH keypair for the out-of-band management network.

- Change into the “2-cloud-init” directory - in here you will find one directory named after each node you created on the canvas in the previous section. Within each subdirectory, simply run the “make” command to generate the ISO file.

- On the GNS3 canvas, right click on each VM in turn and select Configure. Change to the CD/DVD tab and select the ISO image you generated in the previous step.

Once this is completed, you will find that all your VM images will have all essential configuration performed on their first boot. However don’t boot all your nodes just yet! For everything to come up cleanly, we need to configure the network in a logical sequence, the next step in which is to complete the configuration of the management node.

Configuring the management node

Right click on the mgmt01 VM and click Start. Leave all other VM’s powered off at this stage. Now when you double-click on it, a console should open and you should see the VM boot up. You will also see it reboot - this is part of the cloud-init configuration which disables persistent network port naming.

Once the reboot completes, you should be presented with a normal login prompt. If you are using the cloud-init examples that accompany this blog, log in with ubuntu/ubuntu. If all has gone well, you will have a clone of the accompanying git repository in your home directory.

In our infrastructure, our management VM is going to perform a number of important functions (as well as running the Ansible playbooks to configure the rest of the infrastructure). It will act as a DNS server for our infrastructure, and also a DHCP server with static leases defined for the Cumulus VX images. It even acts as a simple NAT router so that our infrastructure can download files from the internet, via the NAT1 cloud we placed onto the canvas.

Assuming you’ve created the infrastructure as described (including the MAC addresses), you can simply change into the 3-mgmt01 subdirectory on the git clone, and run the Ansible playbook as follows:

ansible-playbook -i inventory site.yml

When the playbook completes, all the functionality of the management VM will be configured, and we can power the out-of-band management switch.

Configuring the out-of-band management network

The out-of-band management switch is a simple, layer 2 switch - however it still needs to be told that this is its configuration. Fortunately, Cumulus Networks’ switches are easy to configure using Ansible, and a playbook is provided in the accompanying git repository. Simply change into the 4-swmgmt subdirectory, and run the playbook as follows:

ansible-playbook -i inventory site.yml

Once it completes successfully, swmgmt will be configured as a layer-2 switch for managing all the other devices on our virtual infrastructure. From here, you can power the other 4 switches.

Configuring the spine-leaf switch topology

Once the 4 switches which comprise the spine-leaf topology boot up, you can proceed to configure them. Once again, Ansible playbooks are provided for exactly this purpose. The switch configuration for these switches is a simple layer-2 MLAG configuration - more advanced configurations are possible and I’ll leave it to you to explore more advanced options - however the code provided in the accompanying repository will set up a spine and leaf topology, with the switch ports configured to support resilient bonding on all the OpenStack nodes. Note that the port configuration assumes you have wired up the virtual machines as discussed earlier in this blog, and you will need to edit the configuration if you wish to change the port assignments.

Once you are ready to configure the switches, simply run the playbook in the 5-swcore subdirectory, as follows:

ansible-playbook -i inventory site.yml

When that playbook completes successfully, you will have a fully configured infrastructure with a resilient switching architecture and bonded network configurations on all nodes. The final stage is to power up all remaining nodes, and to install OpenStack.

Deploying OpenStack

With the switching infrastructure set up, you should now be able to power on all remaining virtual machines. They will obtain all their initial configuration (including networking) from the cloud-init ISO’s we attached earlier, and will present themselves as a blank canvas on which OpenStack can be installed. It is worth noting that although I have created this as a worked example for OpenStack, you could use this to simulate just about any distributed architecture.

Installing OpenStack, even from the openstack-ansible project, is a fairly lengthy and involved process. All details are given in the README.md file of the 6-osansible subdirectory of the GitHub repository accompanying this article, so we won’t repeat them again here.

In short the process involves cloning the openstack-ansible code onto the management node, preparing the node for OpenStack deployment (a special bootstrap script is provided for this), setting appropriate variables to configure the installation, and then running the playbooks in the correct sequence. If you’ve never done this before, this can be quite a daunting task, especially when you come across issues such as the incompatibility between ceilometer and the ujson Python module that exists in the openstack-ansible 19 release.

A great deal of credit goes to the team that manage the official openstack-ansible IRC channel, without whom the creation of this demo environment would not have been possible.

Wrapping up

Although the nested virtualization that this setup takes advantage of can at times be slow, and the hardware requirements, especially in terms of memory and I/O performance are significant, the techniques we have covered here offer great potential for both training, and development purposes.

For example, you could build a real production OpenStack configuration on physical servers, using real physical Cumulus Networks powered switches using most of the same playbooks and cloud-init configuration data that we have used here. Similarly, you could simulate your production environment in GNS3 on a suitably powerful host, thus performing penetration testing, or testing new configurations, or even failure modes, to see how the environment responds. For example, you can easily power down entire sections of the GNS3 virtual infrastructure, or delete connections, in full confidence that you are not going to (accidentally or otherwise) impact any other vital services. The environment is a complete sandbox, and so is ideal for security testing, especially if you are investigating the impact of certain kinds of attacks or malware.

The opportunities provided by this kind of setup are endless, and the kindness of Cumulus Networks in making Cumulus VX available for free means you can easily simulate your real network infrastructure in a contained, virtual environment.